In late 2022, I was eating dinner at a Thai restaurant with some friends. You know the one—with the lotus flowers and Buddha statues dispersed innocuously around the restaurant to offset the imminent toiletry turmoil.

Having just completed my university degree, I was asked the eternally predictable question: What’s next?

“I want to build companies,” I said without hesitation.

Much to my chagrin, this answer was met with smirks. “Straight to the top huh?”

Like every other idea-filled go-getter who spends too much time on Twitter, I’d adopted the idea that starting a company was my only pathway to a life of freedom and autonomy. By this point, I’d watched Silicon Valley three times and read the first half of The Almanack of Naval Ravikant, so I (obviously) knew what it took to build a company.

I wasn’t a founder determined to fulfil a vision. It didn’t matter to me whether I sold software or gluten-free edible panties. I didn’t have grand a vision for a world-changing company that I earnestly believed in. All I cared about was freedom and autonomy.

In my mind, this meant never stressing about money, getting more time with my partner and family, and being able to sit and read for hours.

And if this was my only driving force, things might have been different. But it wasn’t enough to start a company in the hope of freedom. I had to be known as an entrepreneur. I needed “Jayson” to be synonymous with “… is an entrepreneur.” I looked at successful entrepreneurs online and didn’t just admire them, I needed to be one too.

“Straight to the top, huh?” Yes, goddamnit!

I: Fear Personified

Like any first-time “founder”, I seesawed between elation and exasperation. By morning, I was an entrepreneur. By afternoon, I was an absent-minded swim teacher who wanted to be back at my desk compulsively working on the business.

The business idea I’d settled on built custom and automated workspaces in an app called Notion. I’d managed some early success, landing some five- and seven-figure entrepreneurs as clients1. But I struggled to retain them. My pitch was “Get your time back so you can focus on what matters.” But in reality, I was building systems that I thought they needed rather than what they wanted.

I was arrogant. But instead of reflecting on the reason for my retention problem—one that threatened to prevent the business from growing—I’d double down and work harder. Even when I’d jolt out of bed at 2 am, unconsciously panicking and sobbing from the stress, it never occurred to me that the issue ran deeper than the mere drive to succeed. Fear, masked by arrogance.

I relied on comparison to motivate me. For example, on February 14th, after solving a challenging technical problem for a client, I wrote to myself:

“Perhaps self-Doubt is ok because it drove me to grind until I solved the problem. For many, that feeling would've made them give up. But for me, it drove me. That's why this [the business] is going to work.”

But comparison is short-lived, soon leaving me motivationally impotent. And so the cycle would go. I’d relentlessly pour myself into my work, only to burn out and feel worthless. Maybe I’m just not cut out for this.

When I reached this point, I’d put my little desperation project aside and begin to notice the world again. I’d sit with a cup of tea with nowhere to be while I soaked up the sun’s warmth and listened to the birds chirping in the trees. Until an idea struck or a new lead came in.

Identity reinvigorated. Work prioritised. Values sequestered.

II: Right Place, Right Time, No Dime

An opportunity presented itself in June, one I hoped to reflect on in some hypothetical documentary and say, “That was the moment that changed everything.”

I’d connected with a big-name entrepreneur in the Twittersphere who’d started an agency and needed help building out their operating systems in Notion. The stakes were high. Landing this client would add serious credibility to my business. I could finally quit my job and live the life I’d been scrapping for. They just needed to see a demo video.

I was eager to close the deal, but fate disagreed. Thousands of ants (you read that correctly, ants) had founded a colony inside the warmth of my laptop. I tried every solution Google had to offer, but it was clear professional intervention was necessary. As I helplessly waited for the laptop massacre to be over, I could feel the pressure throbbing in my head and constricting my chest.

Finally, on the day of The Great Ant Exodus of ‘23, I received an innocuous bump from the agency: “Please don’t forget to walk us through your demo!” But all I read was: “Today or not at all.”

Shit a brick.

Originally I’d planned on building something from scratch, just for this demo. But I had less than an hour before work. Luckily I had something analogous built out for a current client. It would have to do. Jump off the cliff and build the plane on the way down, eh?

It was going so well. The recording was perfect: Clear, concise, and conveyed why I was the person to help them.

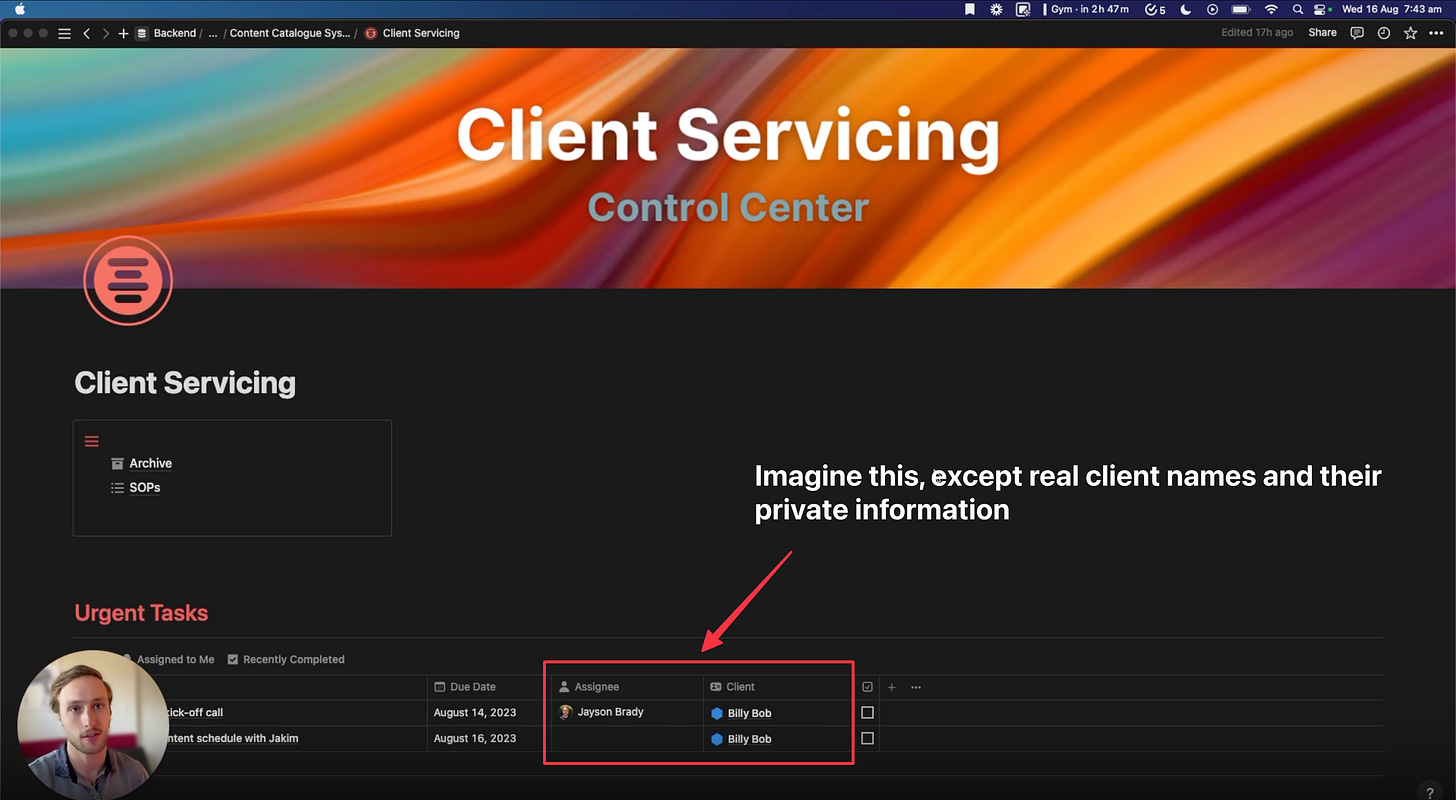

But as I rewatched, my partner pointed out that client names were visible. Plus the video recording software wouldn’t allow me to blur the names out.

Shit a bigger brick.

My stress reeked. This was an otherwise perfect demo. I needed to land this client. My entire being depended on it. I knew the right thing to do, yet I was prepared to disregard it. Maybe it’s not that bad. Only one other person will ever see this.

Back and forth we went as my partner implored me to see virtue. No, it is that bad! I wouldn’t want my data shared like this. The angel on my right shoulder was trumping the devil on my left. I was going to have to re-record the whole goddamn thing. What am I going to do I have to leave for work soon I don’t have time to re-record I should call in sick but I desperately need the money what do I do what do I do?!

I started screaming, “FUCK! FUCK! FUCK! FUUUUUCK!!!”2

Ooft…

I wish I could say this moment was unique—a shocking scene in the documentary where the protagonist retrospectively admits, “That was the moment when I realised how bad I let things get,”—but it wasn’t. I had become a stressed little “gremlin boy.”3

I figured my stress was a byproduct of being “in the arena”, never entertaining the possibility that these moments were never really about the business. I was desperate for validation, anything that offered to reinforce the precarious identity I’d cloaked myself in.

But why was such an identity necessary? What was I trying to hide or protect?

I already had everything I needed: The perfect partner, a loving family, a decent-paying job, no health issues. And yet I would willingly trade my sanity for anything that offered to welcome me into its embrace and whisper, “There there child, I can tell you who you are.”

To answer your question, I ended up submitting the demo with the names blurred out. But it was all for naught. After months of emails and calls, I didn’t land the client. For this and many other reasons, it was the beginning of the end for my business.

On the 6th of September, I wrote:

I’ve been white knuckling this business idea for so long I feel no clarity in anything. I feel directionless every day. Frequently I say to [my partner] “what the fuck am I doing? I’m poor, and for what?”

The business was dead, but the little gremlin boy was not.

III: To Hold Your Breath Is To Lose Your Breath

Even after the business ceased and I had accepted the fact that I was going to have to get a “normal job”4, I still searched for prospective identities to fortify my capricious sense of self.

“Maybe I’ll become a product manager! Or maybe I’ll work to become a COO—I might not be cut out to be a CEO, but I think I could be a number two, right?”

Then I read something from Alan Watts, the great Eastern philosopher, that changed everything:

“If I want to be secure, that is, protected from the flux of life, I am wanting to be separate from life. Yet it is this very sense of separateness which makes me feel insecure. To be secure means to isolate and fortify the "I," but it is just the feeling of being an isolated "I" which makes me feel lonely and afraid. In other words, the more security I can get, the more I shall want.

To put it still more plainly: the desire for security and the feeling of insecurity are the same thing. To hold your breath is to lose your breath…

We look for this security by fortifying and enclosing ourselves in innumerable ways. We want the protection of being "exclusive" and "special,"... These defences lead to divisions between us, and so to more insecurity demanding more defences.”

Everything I’d been doing—not just trying to build a business, but every other passionate pursuit before it—was an attempt to answer the question: “Who am I?”5

It felt crucial that I have a sturdy answer to this question, just in case camera crews came bursting into my house demanding justification for my existence. “Mr Brady! Mr Brady! What do you have to say for yourself?” You know, normal person worries.

I came to realise that this is an absurd question. It implies that action is required. But in reality, there’s nothing to do.

The answer was right before my sizeable nose the whole time. I already knew what mattered to me, what my values were. They were the things I claimed to be the driving force of the business: Time with my partner and family, freedom, and so on. All I had to do was behave accordingly.

I value spending time with my partner. So then the answer was not to spend all my time neglecting her to build a business in the hopes of spending more time with her; the answer was to spend time with her. I value freedom. So the answer was not to forgo the freedoms I already had in the hopes of maybe producing greater freedoms in the future; the answer was to gratefully enjoy my existing freedom.

The whole thing was a contradiction born from the attempt to protect myself from the uncontrollability and unpredictability of life. The problem wasn’t in trying to be something special, but rather in trying to be anything at all. Only once I realised this did the gremlin boy finally perish.

As I began to genuinely focus on my values, I realised that “Who am I?” is a profoundly boring question. It doesn’t matter. Worrying about identity offered me nothing, but mindfully participating in life and engaging in the lives of others gave me everything.6

As Watts later says in the book:

“… the mystery of life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.”

If I can highlight one thing, it’s this: My partner is the hero of this story. She tolerated a lot during this period. She was consoling and nonjudgmental of my self-inflicted breakdowns. She was patient even when I declared that I was going to skip out on Christmas to work on the business. And she was kind and loving not only when my heart, but also my brain, was two sizes too small.

As I waddled around like a clueless toddler chasing ducks, she sheep-dogged me away from inevitably toppling headfirst into a pond. The fact that I have come out the other side with any character growth is mostly owing to her.

This figure is the revenue those entrepreneurs had generated in their businesses, not what I earned from working with them.

This is a reference to a throwaway comment made by George Blackman as he reflected on the story of founding his scriptwriting agency. George describes this situation where he couldn’t stop working, not even for a 20-minute car ride with his girlfriend and her mum. He sat in the back of the car rudely (his words) continuing to work, saying, upon reflection, “I’d become this stressed little gremlin boy.” I remember watching this about seven months after I’d stopped Timeful and feeling like it was completely analogous to the relentless sense of urgency I’d felt (You can watch for yourself at the 5:55 mark onwards).

To be clear, I have nothing against normal jobs. But at the time I despised the idea of having to work 9-5. It felt like I was forfeiting control over my life.

Watts says: “To understand that there is no security is far more than to agree with the theory that all things change, more even than to observe the transitoriness of life. The notion of security is based on the feeling that there is something within us which is permanent, something which endures through all the days and changes of life. We are struggling to make sure of the permanence, continuity, and safety of this enduring core, this centre and soul of our being which we call "I." For this we think to be the real man-the thinker of our thoughts, the feeler of our feelings, and the knower of our knowledge. We do not actually understand that there is no security until we realize that this "I" does not exist.”

This is not to say that “The Self” doesn’t exist, just that a fixed identity that persists over one’s entire life doesn’t exist. Ergo, “Who am I” is a tedious (and thus unimportant) question because you’d be forced to ask it daily when you need not.

In ‘One Blade of Grass: A Zen Memoir’, Henry Shukman says, “I was slowly beginning to understand that Zen wasn’t just about meditative absorption and insight, nor was it something done alone. It was about activity, about how you lived and interacted, how you treated others. It wasn’t enough to “be enlightened,” whatever that might mean; what counted was living it.”